Adapted from: Metcalfe, J. (2017). Learning from Errors. Annual Review of Psychology, 68(1), 465-489. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010416-044022

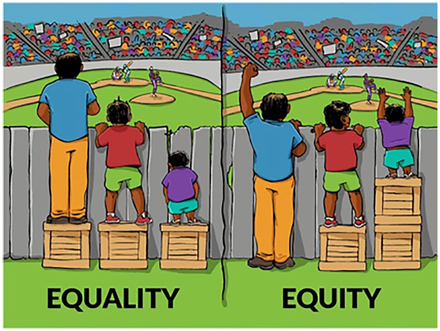

Educational research has begun to recognize the value of errors in learning. In this context, the work of Janet Metcalfe, particularly her article Learning from Errors, is essential for understanding how errors can act as catalysts for meaningful learning when managed effectively.

A key aspect of her work—and one of those counterintuitive ideas we love to highlight—is the hypercorrection effect, a phenomenon suggesting that errors made with high confidence can become particularly effective learning opportunities when appropriately addressed. In other words, the higher the confidence in the error, the greater the corrective effect.

What is the Hypercorrection Effect?

The hypercorrection effect refers to the tendency of individuals to better remember the correct answer after correcting an error they initially responded to with high confidence. According to Metcalfe and collaborators (Metcalfe & Finn, 2011; Butterfield & Metcalfe, 2001), this effect arises from a combination of metacognitive and emotional factors that strengthen memory when there is a discrepancy between expectations and actual outcomes. This idea connects to our discussions in previous posts on cognitive biases.

The hypercorrection effect suggests:

- High initial confidence: Errors made with high confidence are especially significant because they create greater cognitive surprise when the correct answer is revealed.

- Increased attention to feedback: The discrepancy between the incorrect and correct answers activates attentional processes, facilitating the deeper encoding of new information.

- Learning persistence: Studies have shown that corrected responses in these contexts are more likely to be remembered long-term, even outperforming correct responses initially given (Butterfield & Mangels, 2003).

Implications for Teaching Practice

The hypercorrection effect underscores the importance of evaluating students’ confidence in their answers. Metcalfe and Finn (2011) provide evidence that confidence acts as a metacognitive cue, directing attention to the most relevant errors. For this reason, educators should integrate mechanisms that allow students to express their confidence levels when answering, such as self-rating scales before receiving feedback. This reflection helps students consider whether their errors stem from uncertainty or from overconfidence.

According to Metcalfe, high-confidence errors create a «window of cognitive plasticity» where corrective information is processed more deeply. This principle aligns with instructional models like the 5E model, particularly during deliberate practice and formative assessment activities.

Additionally, studies by Butterfield and Metcalfe (2006) indicate that the emotional response to discovering an error can act as a learning catalyst. The positive emotional impact of resolving an error reinforces the memory of the correct answer.

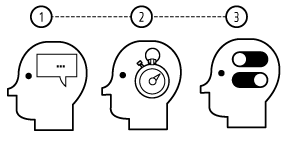

Three Strategies Based on This Research

- Design Challenging Questions with Immediate Feedback

To maximize learning, design questions that allow students to make reasonable errors. These should be accompanied by immediate feedback that explains the correct answer and the reasoning behind it. - Incorporate Metacognitive Confidence Measures

Include activities where students rate their confidence in their answers. This can help identify high-confidence errors that can be leveraged through the hypercorrection effect. - Leverage Retrieval Practice

Retrieval practice is an ideal tool for harnessing the hypercorrection effect. Students who respond to open-ended questions or practice tests and then receive immediate feedback are more likely to consolidate correct answers effectively, especially when they initially made high-confidence errors (Roediger & Butler, 2011). For more examples of retrieval practices, check out this post.

Limitations

While the hypercorrection effect holds great potential for improving learning, it also presents practical challenges. Not all students respond equally to feedback, particularly in high-anxiety environments or in settings with a strong performance orientation. Moreover, the effect seems to depend on the quality of the feedback and students’ willingness to reflect on their errors.

For this reason, Janet Metcalfe emphasizes that effectively implementing these strategies requires an educational environment that values errors as an integral part of learning rather than as markers of incompetence. This approach is particularly relevant in contexts where feedback is immediate and specific, such as classroom activities or one-on-one reflective sessions with students.

References

- Butterfield, B., & Metcalfe, J. (2001). Errors committed with high confidence are hypercorrected. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 27(6), 1491–1494. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.27.6.1491

- Metcalfe, J., & Finn, B. (2011). People’s hypercorrection of high-confidence errors: Did they know it all along? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 37(2), 437–448. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021962

- Huelser, B. J., & Metcalfe, J. (2012). Making related errors facilitates learning, but learners do not know it. Memory & Cognition, 40(4), 514-527. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-011-0167-z

- Metcalfe, J., Xu, J., Vuorre, M., Siegler, R., Wiliam, D., & Bjork, R. A. (2024). Learning from errors versus explicit instruction in preparation for a test that counts. British Journal of Educational Psychology, bjep.12651. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12651

Deja un comentario